|

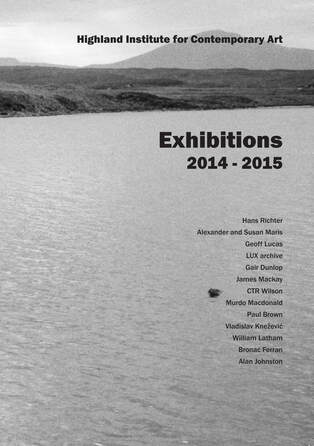

The Highland Institute for Contemporary Art (HICA)

|

|

View of HICA

A brief summary of the HICA project is provided here. Geoff Lucas’ PhD study, Towards a Concrete Art, gives a fuller account of the project in its gallery phase, up to 2015, the year the PhD study was completed. The study follows the structure of HICA’s exhibition programmes to examine understandings of Concrete Art in the context of relevant philosophical inquiry and findings from recent science. It provides provisional conclusions regarding HICA’s activities and the project’s proposed revision of Concrete Art’s theoretical basis, seeing potential for a process-based interpretation.

HICA Geoff and Eilidh Lucas began their collaborative practice in 2007 after moving to an isolated rural location in Scotland, where they devised and initiated the Highland Institute for Contemporary Art (HICA). HICA formed an extensive relational artwork that provided a framework for examining their artistic concerns: conceived as a means to explore a process view of the Concrete, it considered ideas of materiality from science and philosophy alongside varieties of understandings of the term ‘concrete’ in the history of art, to reflect on the nature of the Concrete and, in general, on our relation to Nature. From 2008 to 2016 HICA operated as an artist-run gallery: it’s curated exhibition programmes were planned in ways to develop the project’s conceptual and theoretical focus, while the activity of presenting exhibitions, working with other artists, audiences, funding bodies and other arts and cultural organisations provided instances through which to consider the ‘concrete’ results of the project’s engagements. Geoff and Eilidh Lucas took these engagements to logically include all interactions with HICA, no matter how slight, as ‘concrete’ activity shaping the overall work. As with the problem of observation in quantum mechanics, where its effects may be taken to implicate the whole world, the question can perhaps be asked as to where the line of involvement should be drawn, if it is to be drawn at all. HICA tested this proposition, through numbers of its exhibitions, and explicitly in exhibitions such as with Daniel Spoerri , Liam Gillick or Grey Area, examining how consequential otherwise ephemeral-seeming connections may be. Examples of HICA projects and exhibitions:

|

|

Daniel Spoerri exhibition at HICA, 2012

Detail of the installation |

|

Wilson Chamber Images: The Aesthetic of the Sub-Atomic, 2015

Presented by Murdo Macdonald Photograph by C T R Wilson showing the tracks of Alpha and Beta rays |

|

The question of the degree of involvement here naturally leads on to questions of what part individual response may play in shaping collective activity, the agency and intention of the individual, and the means through which these communications are enacted. These questions HICA understood to have parallels in biology and physics, with investigations of the intelligence of individual entities, ranging from larger animals to plants, fungi , single-cell organisms, and in some cases even consideration at atomic scales, being matters of contemporaneous scientific research. This research has equally investigated how individual intelligences are then incorporated into larger structures, to display what may be judged collective intelligence; whether this might be bacteria or cells in a body, ants in a colony, birds in a flock etcetera.

Here HICA considered itself as subject of its own experiments. It investigated its own activities and engagements as art-related phenomena, in some way equivalent to the phenomena in these scientific studies; this parallel research provided a mirror to HICA’s own inquiries into art’s role in forming interventions into living processes, interventions which result from the decisions and choices made by individuals. Naturally, an important additional aspect to this artistic inquiry was consideration of the question of artworks’ ability to themselves form communications within these processes, how they may embody meaning and intelligence to then be interpreted by an audience. Within HICA’s experimental approach then there was particular concern with an individual’s experience of agency; a reflection on how individuals may input into more general processes of shaping, through artworks and their extended meanings, and how these interventions are made through dialogue with other entities and circumstance; a mutual relationship of communication and influence. HICA termed this a ‘gardening’ process, where intentional actions of the ‘gardener’ intimately tie-them-in to the resulting ‘garden’ (in whatever form it takes); a concrete experience of reaping what is sown (again, in dialogue with other entities and circumstance), apparent at differing scales of operation; from cells to larger structures; individual, collective, societal, cultural, and so on. Aesthetic choice and preference thus became a focus for the project as a basic process through which individual agency might shape complex systems; a non-mechanistic and experiential means of self-organization, an intelligence-based evolution operating through external, that is to say, epigenetic, influence. For HICA, this means of self-organization appeared entirely fitting to its own concerns with revised understandings of the ‘concrete’, and the processes of a ‘concrete’ art. |

|

HICA exhibition:

Richard Roth, 1 May - 5 June, 2011 Vernacular Modernism, detail of installation (colour chart) |

|

Considering varying forms of what could be understood as ‘artistic’ behaviour, as aesthetic influence in decision-making, from perhaps very basic choices made by microscopic organisms to more conscious modes of behaviour in larger animals and the diverse forms of what we generally take to be art-practice in humans, further provided HICA with an ideal subject for consideration as regards our relation to Nature. For example; how an entity identifies itself as different from its surroundings, how individuals negotiate competition in fulfilling their needs, how an individual vision could, perhaps dangerously, misalign with the requirements of its environment, and whether an entity’s growth and sense of progress is always at the expense of its environment, appeared dilemmas that might all be seen to have an aesthetic aspect.

HICA’s gallery programmes were thus structured to consider human artistic behaviour as something perhaps ideally representing the difficulties here. While these dilemmas may exist around any entity’s existence and development, Geoff and Eilidh Lucas see the potential conflicts here exemplified by human art practice: the making of artworks, their presentation, may necessarily require or at least strive for a particular sense of exceptionalism, an exceptionalism that appears equated at times with an inescapably dualistic sense of mind: an anthropocentric idea of human consciousness, a conception of ideal form or beauty separate from the world, or requirement for novelty that stands apart from, or confronts, what may be perceived as the mundane realities of the physical world. Here then, in our current culture at least, there appear immediate relational problems around identifying something as an artwork, or someone as an artist, where most often value only appears to be attached to art in-so-far as it conflicts with its environment (regardless perhaps of the wishes or intentions of the artist themselves). That is, very often it seems in our current culture, human aesthetic choice appears allied to a philosophy, not just of separation, but of escape. HICA thus re-examined this sense of dilemma, putting under the microscope all personal and professional choices and behaviours, of Geoff and Eilidh Lucas, as the project’s directors and curators, as well as all contributors to its programmes. It viewed this background of activity as similar, and in some ways equal to, the decision-making processes made by the contributing artists in the development and presentation of their artworks. The project further reflected on the dynamics of the relationships that formed through this activity: what might be judged beneficial in terms of relationships, or detrimental; how, at different times, the contributing artists or the gallery, might be seen to feed-off of the other; how, and when, exploitation of the other might be judged negative for the project, or positive; how the state of the gallery and its exhibitions developed knock-on effects for cultural life, locally and more widely; what was necessary for preserving the dynamism of these relationships and the project as a whole, maintaining the life of the project as a vital entity, and so on. Again these observations were equated to the way in which an artwork, in whatever form, might also be developed as some sort of vital entity. Rather than then dwelling on arguments for or against individuality, for instance Concrete Art’s historical rejection of individuality against contemporary art’s greater requirement for personal expression, HICA looked to individuals’, and art’s, roles in contributing to the healthy functioning of the wider, organismic, whole: it judged the positivity or negativity of these relationships in terms of process, proposing that ‘mind’, ‘beauty’, and novelty may all in actuality be functions of a harmonious engagement with the world’s self-organising process, even if, perhaps, as with our illusory sense of ‘self’, these may appear qualities of some separate realm. |

|

HICA exhibition:

Jeremy Millar, 2 May - 6 June, 2010 Still from Preparations, 2010 |

|

As part of the HICA project Geoff and Eilidh Lucas maintained a vegetable plot in the garden surrounding the buildings, adjacent to the gallery. They had jointly kept an allotment for some years prior to running HICA, and now maintain vegetable plots as part of the garden at the site of their EQ project, in France, though this space at HICA was declared to be fully part of the gallery project: for HICA it formed a particular statement of a concern with the connections between theory and practice. HICA understood theory and practice to be differing points on the same scale, judging each to be informed by the other and without any real, Cartesian, division between the two. The garden thus formed a parallel to the HICA gallery making cross-overs of observations readily available between them. Such things as HICA’s nomination of a ‘gardening’ process, in terms of interventions through aesthetic choice, could thus be viewed in the light of both literal involvement in gardening processes and/or artistic and cultural activity. Similar observations informed consideration of, for instance, the actions and interactions of individuals, asking how and when individual action may be subsumed into the collective; the nature and means of behavioural shaping, and what it is to have agency; how both simple and complex lifeforms respond to their environment, or act in some congruent way with it, through dialogue; what the nature of this ‘dialogue’ might be and where and how intelligence might be located within it; if and how intelligent responses differ from more bodily responses to the physics of the world, how both micro and macroscopic entities may experience effects originating at the scale of the subatomic (the domain of what has been termed ‘quantum biology’), and so on.

|

|

View of the HICA vegetable garden

|

|

At the same time the garden space provided perspective on the overarching concern with our current sense of relation to nature, where a contemporary human conception of a garden, as well as the techniques, materials and tools (and fuel) required to maintain it, may appear in stark opposition to what a healthy ecosystem requires. Perhaps a ‘white-cube’ gallery space is equally removed from a ‘healthy’ experience of art? (Both perhaps exhibiting our desire for separation, if not escape from the world.) These states may prompt us to question how our own communications with and understandings of the world around us have gone so far awry. Again, the combination of the HICA garden and gallery provided overlapping contexts for engaging with these questions, reflecting on accepted current approaches in both spheres and exploring how things may be negotiated differently in future. The developing cultural shift in modern approaches toward gardening and agriculture, for instance, continued through the period of activity of the HICA gallery (from 2008 to 2016), with ideas of less environmentally damaging means, such as methods of permaculture, formulated through the last century, beginning to permeate into more mainstream discussion. HICA’s particular focus was how the aesthetic aspect of this discussion was, and continues to be, adapted: how the acceptability of industrial farming methods may be changing, with the understanding of the need to disrupt monocultures, planting strips, borders or hedges for native species and biodiversity, and moving towards smaller-scale production, organic farming, regenerative agriculture, ‘no-dig’, food forests and re-wilding. Those who maintain gardens or green spaces may equally be aware of the need to move away from the sterile and overly-manicured. Questions of what is appropriate maintenance of the ‘green deserts’ of lawns for example, may force a reconsidering on behalf of society in general of what the desired end is; what is the philosophy underlying our current sense of a ‘proper’ approach and how might a different visual appearance cause this philosophy to shift? Changes in understandings of the importance of soil, from being ‘dirt’, to being an essential, living, life-giving and life-supporting ecosystem, might best illustrate the potential here for a radical re-think in relation to the necessary ‘mess’ of life and the earth.

For HICA, it was shifts of this kind that, seen alongside the history of Concrete Art, suggested a necessary reconsideration of Concrete Art’s scientific and philosophical alignment: how and why might Concrete Art be identified, most readily, as in sympathy with the controlled and mechanistic, and are there ways to distinguish within it alternative sympathies, with a closer alignment to the processes of Nature? A very brief outline of this reassessment, particularly as relevant to a discussion of the HICA garden, is given here, as part of this summary of the HICA project: |

|

Examples of events at HICA

|

|

The identification of a ‘concrete’ art stems from the observation of varieties of inherent meaning in the things of the world: if isolated examples of these meanings might in some sense be ‘non-representational’ they are not then understood to inhabit some other, ‘abstract’ realm, but are seen to be concretely present; a function of the physics of the things themselves. That those in Western art traditions who first developed this ‘concrete’ art sought to grasp these meanings through a semi-scientific study of their occurrence in basic forms, indicates just how close the possibility of certain identification seemed to them. A formal language, thus devised, might then be employed to spread a more ordered and sanitary vision: a New art, equal to the science building the New world. The works of these originators are thus frequently visually congruent with the measured and engineered, appearing to desire some equivalence to a mechanistic idea of science, and to be part of that same cultural project, aiming at control over Nature.

But to say that the impetus for a concrete art is the encountering of meanings in the world, in HICA’s assessment, immediately sets their methodology against the received methodologies of mechanistic science. While these artists’ strategies might absent self-expression as much as possible from their work, intending objectivity, to obtain clearer focus solely on these meanings, the act of engaging these meanings in-itself requires the artists to remain within, if not intensify, their relation with the world, heightening their awareness and emotional response. This, it seemed to HICA, is significantly different from the intended objectivity of scientific method, which attempts to close off this relation, and the emotional or sensory information it entails. In this way the Concrete artists remain inevitably grounded in ‘feeling’ and aim to increase rather than diminish their empathy with the world; they may be artists who “think and measure”, but their methods naturally tend toward the expansive rather than reductive. It is notable for example, that in pursuing these meanings their works do not tend to narrow down on isolated details, in a scientific manner, for long, but rather tend to lead them to engage greater complexity in work beyond the studio; into other disciplines or media, such as architecture or film, and into messier real-world engagements; ‘the streets will be our brushes, the squares our palettes’. Van Doesburg’s ‘Elementarist’ approach, as example, perhaps partly responsible for the white-cube art-space as ‘laboratory’ for experimentation, could be contrasted with his equal desire to integrate the experience of art into everyday life and remove art from the gallery altogether. If these first manifestations of an attempted scientific Concrete Art, by these means, then seem wrong-headed it may be that this was never their real intention. Perhaps Van Doesburg, for example, was aware that science’s Classical understandings were being outmoded. Though it is the case that others taking his Concrete Art forward, with awareness of the unfolding fundamental shifts in understandings of physics, have, at various points, continued to seek some equivalence in their work to science, some handle on the chaos, uncertainty, and indeterminacy of life. The beginnings of the computer age, for example, afforded new means to grapple with complexity, and efforts continue in this vein; suggesting that if we only had enough data and the right tools then we may still develop a clearer, more true picture of the messier parts of life. But for HICA there seems an opportunity to provide an overall more useful way to consider both this general area of concern and works such as those of van Doesburg, taking his works as a most pertinent example. A misunderstanding of his motivations appears made by those who see his Manifesto for Concrete Art, of 1930, as a clear statement, and miss its contradictions and ambiguity. Throughout his work his more ordered Constructivist side is in dialogue with his Dadaist side. This activity undercuts readings of his Concrete Art as a dry attempt to scientifically apply a formal language: he, at times, also states his opposition to Functionalism, and rejects the mechanistic in favour of his primary focus, the aesthetic. In this light the contrasts of De Stijl, their verticals and horizontals, may instead be related to our general experience, and our understandings of how things may be more harmoniously ordered, from a human perspective, while at the same time demonstrating some overall sympathy with what modern physics has since described; our limited and Classical apprehension of a world we know in truth to be vastly more complex. This contradictory nature perhaps seeks to engage a state that is neither this nor that: in philosophical terms, neither Nominalist nor Realist, monist nor dualist, conceptions which might too easily divide the world between inert matter and mind. Rather, this contradictory state may suggest the concrete as process, in which apparent order is developed though change and uncertainty: a process view may be a ‘best fit’ in explaining the apparent relation to phenomena, generally taken to be the territory of science, in this approach: it would maintain its fascination with the structures of meaning encountered (as the means of navigating processes of living at varying levels) but rely on the sensory and experiential interpretation of these phenomena in ways that, by our current ideas of science, are notably unscientific, and, overall, promote the aesthetic. Working between its gallery and garden spaces, HICA sought to further explore how this sense of a process-based concrete art might be developed, to some practical extent accepting our ‘classical’ experience of the world and its consequent aesthetic of order, but, in the way of contrasts and contradictions, also admitting underlying, fundamental, complexity and uncertainty, on which this same aesthetic is also intimately reliant. The basic means of this mode of art would be its operating through the aesthetic choices of ‘artist’ or ‘viewer’, in some way comparable to the negotiations of environments by other organisms. Geoff and Eilidh Lucas continue to formulate this approach. They propose it as a coherent development of the work of many of the originators of concrete tendencies (if not perhaps always in agreement with their stated intentions), while it also provides consistency with the ongoing cultural and scientific shifts away from a mechanistic world-view. This identification’s future development suggests further reflection on its relation to science, considering how ideas of science itself may now be open to change: recent scientific research appears confirming of possibilities to attune to sensory information, and develop greater familiarity with concrete means of communication and understanding, between ourselves and the world: for example, demonstrating cells’, simple organisms’ and plants’ integration of environmental information without brains or neural networks. Research of this kind highlights the level of communication which HICA would argue is also the focus of a concrete art: something we also experience and may be constantly immersed within, in our involvements in relational processes and in our general negotiations of our surroundings. Through greater familiarity with communications of this order we may also gain perspective on how we, and all other organisms, operate as part of an overall world-process. |

|

Examples of HICA publications

|

|

A significant further implication of this view suggests decisions resulting from this level of interaction as very much more contingent than might generally be desired in science: moments of navigation of a developing process rather than the discovery of pieces of a fixed jigsaw of truth: this sense of truth may always seem tantalisingly within reach, as we encounter and negotiate structures of meaning, but may, due to the nature of the process itself, ultimately remain elusive and beyond our grasp; one piece of the jigsaw comes into focus as another slips out of view. Responses might just reveal the way ahead at a particular moment, with an eye on both the immediate interactions and the wider picture of the well-being of the whole. If this is the case it may also suggest our current mechanistic science as, in its own way, an equally limited view, despite its efforts to move beyond this state, while it also offers a critique of our science’s methods; in focussing intently on discovering facts (a necessarily reductive intent) it seems it may inevitably be prone to discounting the wider picture and its inescapable complexity.

Thus, the HICA project sought to address its social, environmental and political concerns through envisioning modes of human activity that move away from the confrontational and exploitative relation to environment and towards, as can be observed with many other forms of life, activities that may be judged functioning parts of the wider process, necessarily providing consequent compound benefits to this process’s general functioning. HICA, through the various strands of its research, sought overall to develop its interpretation of a ‘concrete’ art and consider what it might indicate as possible directions for the future. This interpretation Geoff and Eilidh Lucas have termed a ‘quancrete’ art. While the phase of the HICA project, as artwork and gallery, ended in 2016, the HICA organisation is still maintained and its curatorial activities continue. Through these and other related activities, Geoff and Eilidh Lucas also continue to explore and define what a ‘quancrete’ art may be. More details on the HICA organisation and project can be found at www.h-i-c-a.org |

|

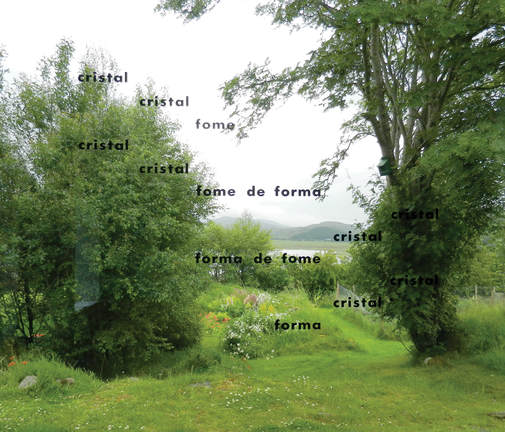

Haroldo de Campos

Cristal Forma, 1958 Presented as vinyl lettering on glass as part of HICA's 2011 exhibition Grow Together: Concrete Poetry in Brazil and Scotland |

© 2024 Geoff and Eilidh Lucas [email protected]